- Home

- Dave Housley

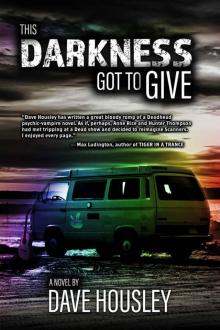

This Darkness Got To Give

This Darkness Got To Give Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

This Darkness

Got To Give

by

Dave Housley

© 2018 by Dave Housley

This book is a work of creative fiction that uses actual publicly known events, situations, and locations as background for the storyline with fictional embellishments as creative license allows. Although the publisher has made every effort to ensure the grammatical integrity of this book was correct at press time, the publisher does not assume and hereby disclaims any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. At Pandamoon, we take great pride in producing quality works that accurately reflect the voice of the author. All the words are the author’s alone.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pandamoon Publishing. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

www.pandamoonpublishing.com

Jacket design and illustrations © Pandamoon Publishing

Art Direction by Matthew Kramer: Pandamoon Publishing

Editing by Zara Kramer, Rachel Schoenbauer, and Forrest Driskel: Pandamoon Publishing

Pandamoon Publishing and the portrayal of a panda and a moon are registered trademarks of Pandamoon Publishing.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC

Edition: 1, version 1.00

Critical Reviews

“Dave Housley has written a great bloody romp of a Deadhead psychic-vampire novel. As if, perhaps, Anne Rice and Hunter Thompson had met tripping at a Dead show and decided to reimagine Scanners. I enjoyed every page.”

-Max Ludington, author of Tiger in a Trance

"Dave Housley has done something remarkable with This Darkness Got to Give. He's managed to combine a compelling procedural, a unique vampire tale, twin portrayals of loneliness and addiction, and a lovely, honest homage to the Grateful Dead and their fans in one outstanding book. I promise you - it's unlike any book you've ever opened. This is a novel you'll read quickly and never forget."

-- E.A. Aymar, author of The Night of the Flood

"A trippy, unique spin on the vampire mythology that'll satisfy Deadheads and noir purists alike."

-- J.L. Delozier, author of Type and Cross, and Storm Shelter

One way or another, one way or another,

One way or another, this darkness got to give.

Garcia/Hunter, “New Speedway Boogie”

Dedication

For Lori, my partner on this long strange trip.

This Darkness

Got To Give

Chapter 1

June 24, 1995. Washington, DC. Robert F. Kennedy Stadium

It was dark outside the van. The blackout windows were illegal but necessary, and since he simply couldn’t travel during the day, it hadn’t been a problem in the twenty-three years Cain had been on tour. Familiar sounds trickled in from the parking lot: somebody playing a bootleg that he identified as the Europe ‘74 tour off to his left; behind him, the terrible parking lot band that had been playing off and on ever since they’d arrived in DC two days ago. Scattered throughout, the buzz and chatter of Deadheads moving along through the lot, their calls advertising goo balls, T-shirts, doses, shrooms, burritos, cigarettes, beer. They shouted, sang, danced, fought, laughed, wept, chanted, chattered crazy, all of it a mere ten feet away from where Cain lay right now. It was the laughter that got to him. It made him nostalgic, then angry. It made him regret what he knew he would have to do later.

Time was important. The life, his very survival, it was all based on time. It would be time to go out soon. Already, he could feel it starting in his fingertips, something between an ache and a tingle. Soon it would spread—inward, moving up his arms and into his gut, up through his spinal column until his head filled with white pain, his body vibrated with agony and adrenaline, and there was only one way to make it go away.

As always, he listened through the parking lot jangle for the high-pitched voice of the one who had sold him his dose. The one who had known, somehow, what he was, had casually mentioned that these doses, his doses, were the only ones that would work on Cain, too. “I know what you are,” the Dealer had said. “I know what it’s like. I can help.”

Cain hadn’t said a thing. The man had read something in his eyes, or the lack of something, and handed him a dose.

Cain shifted in his bed, sat up. He listened. “Shrooms doses shirts hey didn’t I see you in Jersey dude that’s my shirt…” An endless stream of the normal chatter. But nowhere that voice he knew he would never forget: “I can help.”

The ache was moving up into his hands, the tingle starting down in his toes. It had been three months since Saint Patrick’s Day and the Spectrum and his dose, through the East Coast and down south and back out west and now back to the east and still no sign of the guy. Not that Cain would be doing anything different—he’d been on tour ever since he had gone through the change, almost ever since the band was touring at all. One thing he had learned: he wasn’t very good at being what he was away from tour. But without whatever the guy had put into him, without that dose—so stupid—everything would be different. It would be normal. Predictable. Controllable. The same careful way he’d been living for the past twenty-three years. One dose, and everything had changed.

He stiffened. Somebody was approaching. Even after all this time, he wasn’t sure if he was hearing it or feeling it. The books, the folklore was…inconsistent. Even what he had learned firsthand tended to fall somewhere in the space between self-help and rumor. He had been told, for instance, that some could fly. The older ones, the strongest. Cain had never seen it, had certainly never felt the release of leaving his earthbound tether and screaming through the black night like a hawk. He didn’t know many of his own kind, had purposefully kept himself apart from the ones who tailed around the tour like lost moons looking for something to orbit again.

<

br /> Knock, knock…knock on the side of the van. Footsteps. Then knock, knock on the other side. It was the girl. It was time. He sat up, put on his Birkenstocks and a tie-dye, cutoff jeans and a floppy hat. He didn’t bother looking in the mirror.

The pain was moving into his gut. Along with it, the feeling of strength, something beyond the usual, something that felt like cocaine, what he remembered of it, like PCP the few times he’d taken it with the Angels, all those years ago. A feeling like he could do anything, like he needed to do something or he’d burn into himself like a black hole. He needed to get out there. He needed to do it, and soon.

The van door opened with a whoosh and shut with a snap. He locked the doors, checked them, picked up the chain from under the van, and looped it carefully through each door. He fixed the padlock and put the key in his pocket. Under the windshield wiper, a note. “RIVER,” she had written.

Cain walked in the spaces between cars, avoided the major avenues crammed with people selling their wares, heads looking for a score, tourists watching the parade, searching for just the right shirt to take home to their straight lives.

A dirty teenager without a shirt grabbed his wrist. The kid smelled terrible—like sweat and weed and rotting flesh. Cain could tell he was dying somewhere. The smell was too much. “Hey, man,” the kid said. He jerked his hand back. “Dude! Your arm is…” His glassy eyes came into focus for just a second. He took a few steps back. “No worries, man. Just looking for a few bucks, you know, but…” he backed up quickly, nodding his head. “Have a good show, dude.”

“Show ended a few hours ago, man,” Cain said. He reached into his pocket, grabbed a twenty, and held it out.

The kid just stood there blinking. He rubbed his hands together like they were cold. “Did they play Rider?” he asked.

“Not tonight,” Cain said. “Cassidy, though. And Bobby sang…” but it was no use, he realized. The kid wasn’t processing any of it. He waved the twenty again and the kid took a tentative step forward. “You should go to the doctor,” Cain said. “Go and…well, just go.”

The kid nodded, snatched the twenty and backed toward the main road. “Have a good show, dude,” he said.

Cain continued through the parking lot, down toward the river. Have a good show, dude. He’d been to hundreds of shows, and every one had been a good show in one way or another. Nothing topped Europe, the early seventies, but these past few tours had been good, and he was relieved that it looked like he’d be able to tour for another decade, maybe, before he had to find a new home. Jerry played differently post-coma, but on the best nights he still had that shine, that tone, something about it different than anybody else.

Before the coma there had been rumors, whispers that Garcia had been through the change and managed to find some rich rock star way to manage the sun. It was ludicrous, of course, but he’d heard the same thing at one time or another about Clapton, Buddy Guy, Miles Davis. Of course everybody wondered about Keith Richards.

He smelled the river before he could see it. He walked between two vans and found the path, saw the light from the girl’s cigarette bobbing in the weedy little stand of trees that lined the riverbank.

“What’s up?” she said. “How far along?”

“Starting to cramp up a little. Need to soon,” he said. He clenched and unclenched his hands. Soon, he knew, the motion would become involuntary. The back of his neck tightened. His head swam and he thought about how good it would feel to be released, to let go.

The girl stood, threw her cigarette on the ground. She stamped her foot on top of it and twisted, then picked up the butt and put it into a plastic bag she pulled from her back pocket. She wore khaki shorts and a white T-shirt with Winnie the Pooh on the front. She had been helping him for the past few months and they had never exchanged so much as first names.

She pointed to the place where the path meandered along a squat stand of bushes and toward the river. “Same deal as the other night,” she said. “Down that path, the little clearing. One dude, passed out. Bad shape.”

Cain nodded. He could feel it getting worse, tightening. “Anything else I need to worry about, you think?” he said.

The girl shook her head. She put another cigarette in her mouth. “No,” she said. “Straight junkie from what I can tell.” She picked her beer off the ground and took a sip. “I don’t think anybody’s gonna miss him,” she said.

Cain nodded. He fished around in his wallet, handed the girl five twenties.

“A hundred?” she said.

“Keep the change,” Cain said, but she was already walking away. “Hope you had a good show!” he shouted.

“See you down the road,” she said and made her way back toward the lights.

Chapter 2

June 25, 1995. South-central Pennsylvania. Chandler University.

Pete dropped his paper in the slot in Professor Peabody’s office door and stood in the hallway. Could that really be it? College, over? He hadn’t even meant to graduate early and now here he was, a few days and a piece of paper away from having to answer all the questions he had been hiding from for the past three years. Most people went into religious studies to find answers. He was dealing with a whole different set of questions.

And now a different set still: where would he live? What would he do? Where would he go for Christmas, even? Without the structure of an academic program, of department parties and the timeline of the semester and Padma feeling sorry enough for him to invite him to the odd graduate student get-together, did he even celebrate Christmas?

He stood in the cavernous hallway, realizing with a jolt that he had literally nowhere to go. The department still smelled like pipe smoke, although in his entire time at Chandler—four years undergrad and three getting his Masters—smoking had never been allowed inside the building. It had always been, for him, a mysteriously comforting smell, and he wondered whether someone in his family, back before the accident, some uncle or grandfather, perhaps even his actual father, had smoked a pipe. He breathed in the department’s smell for maybe the last time: pipe, books, cheap disinfectant—and took some solace in the fact that even if the smoke smell wasn’t so much a memory as the ghost of one, the faintest whiff of a memory; at least it was a happy one.

The photocopier started up in the department’s waiting area and Pete wandered toward the door. Inside, Mrs. Lin, the rotund, bespectacled administrative assistant who had been running most aspects of the department since the day he wandered through these doors as a freshman, stood waiting for copies to finish. Pete was suddenly overcome with emotion. Mrs. Lin. She looked exactly the same as she had on his first day of classes. There was nothing she didn’t know. In many ways, she was the living, breathing, never-aging heart of the entire department. He realized with a rush that there was a very good chance he would never see her again.

He walked through the door and she looked up from the machine.

“Mrs. Lin,” Pete said. “Well, I just turned in…”

The phone rang and she nodded curtly to him, picked it up, and shouted something in Mandarin into the receiver. She hung up the phone. “If you have to leave paper,” she said, “find your professor door and throw through slot.” She mimed the act of depositing a term paper through an opening.

Pete nodded and she bustled down the hall.

With nothing else to do, he wandered down the stairs and followed a group of laughing sorority girls through the massive old doorway of Glatfelter Hall and out into the quad. Campus had been emptying for the past several days as students took finals and headed back to wherever they were from, back to families and holidays and dinners, to friends and old hangouts, to girlfriends or boyfriends. They lived two lives, he thought—school and home—with the attendant trappings of each, the friends and lovers and couches and beds and posters. In this way, he was a simpler creature. He had just the one life, just this, his classes and his apartment and Padma and Mrs. Lin and Professor Peabody. His world was as limited, as prescr

ibed and precise as the territory of a caged hamster.

He sat down in front of the library and felt the spring air—light and warm, like a cushion all around him. That’s what Chandler was, he thought: a cushion.

A boy and girl walked by holding hands and he wondered what Padma was up to right now. Probably sitting around the kitchen table with her mother and sisters, laughing and drinking wine, like a scene from one of the romantic comedies she occasionally made him watch. She had never really explained why she had to leave so quickly, but he knew she would be in touch whenever her business in New York was done. He had no experience of his own, but he’d seen enough movies, heard enough about Padma’s sisters to understand that families were complicated.

He looked back toward Glatfelter, looming like a castle in the dusky sunshine, a few offices still burning bright and warm. On the steps, a lone figure stood, looking straight at him. It was a man—tall, dressed in a suit and an old-fashioned fedora. He looked like a private detective from a black-and-white movie.

Pete stared and the man stared back. His fingers tingled and he squeezed his hands together. He had an urge to go see the man, find out what he was doing up there, but he put it out of his head. Must be somebody’s father, he thought, checking out campus while their kid stuffed dirty clothes into garbage bags for the trip home.

He still had the apartment, at least. He would go back and watch movies for a few days, maybe start googling PhD programs. Peabody had gone to Georgetown. Maybe there was a place for him there. He could do worse than emulate Professor Peabody’s trajectory. He turned back to Glatfelter and the man was gone.

He watched a butterfly drift along the well-tended hedges. So this was it. His last day as a student at Chandler. He owed the place everything. He had wandered in a broken boy, and even if he knew he would never be wholly fixed, the place had healed him enough that he would go out into the world and…do what, exactly?

This Darkness Got To Give

This Darkness Got To Give